Percentage of People That Can Read Sheet Music

Musical literacy is the reading, writing, and playing of music, besides an agreement of cultural do and historical and social contexts.

Music literacy and music education are frequently talked nigh relationally and causatively, even so they are not interchangeable terms as consummate musical literacy too concerns an understanding of the various practices involved in teaching music educational activity and its impact on literacy. Fifty-fifty and then, there are those who argue[1] against the relational and causal link between music education and literacy, instead advocating for the solely interactional relationship between social characteristics and music styles. "Musical communications, like verbal ones, must be put in the right contexts past receivers if their meanings are to come through unobscured"[2] which is why the pedagogical influence of educational activity an private to become musically-literate might be confused with overarching 'literacy' itself.

'Musical literacy' is likewise not to be confused with 'music theory' or 'musicology'. These two components are aspects of music education that ultimately act as a ways to an finish of achieving such literacy. Even then, many scholars[iii] debate the relevancy of these educational elements to musical literacy at all. The term, 'musicality', is again a singled-out term that is split from the concept of 'musical literacy', as the mode in which a musician expresses emotions through performance is not indicative of their music-reading ability.[iv]

Given that musical literacy involves mechanical and descriptive processes (such as reading, writing and playing) as well as a broader cultural agreement of both historical and gimmicky practice (i.eastward. listening, playing, and musical interpretation while listening and/or playing), education in these visual, reading/writing, auditory, and kinesthetic areas can work in tandem to achieve literacy as a whole.

'Musical literacy': A history of definitions [edit]

Understanding of what the term, 'musical literacy', encompasses has developed over time as scholars invest fourth dimension into research and fence. A brief timeline — as collated by Csikos & Dohany (2016)[5] — is as follows:

- "According to Volger (1973), the fundamental components of musical achievement are "tonal and rhythmic literacy (the ability to musically hear and feel what 1 reads and writes in notational forms)".[vi]

- "In Lee and Downie'south (2004) piece of work, music literacy refers to a bones musical skill, namely reading music scores".[7]

- Herbst, de Wet & Rijsdijk (2005) debate the "relative weight or importance of written (as opposed to oral or instrumental) music literacy [among music educators]".[8]

- "According to Telfer (equally cited in Bartel, 2006), the definition of music literacy has inverse from reading the pitches and rhythms to reading the 'significant of music'".[ix]

- "In the field of music education, the [Hungarian National Core Curriculum] (2012) prescribed different components of music literacy such as history of music and music theory".[ten]

- "The New National Standards for Music Educators (Shuler, Norgaard & Blakeslee, 2014) used the term literacy in a very broad sense; as well including the traditional learning targets such as reading and writing musical notation, it also involved the evolution of then-called artistic literacy".[11]

- For Csikos & Dohany (2016), "the term music literacy refers to culturally determined systems of knowledge in music and to musical abilities. The assessment of such a complex phenomenon requires various approaches in regard to what and how to appraise (a) factual knowledge and musical abilities as defined by experts in the field, [and] (b) knowledge components determined by societal needs".[12]

Scholars such as Waller (2010)[13] besides delve farther into distinguishing the relational benefit of unlike mechanical processes, stating that "reading and writing are necessary concurrent processes".[14] The experience of learning how to "read to write and write to read"[15] allows students to become both a consumer and producer where "the music was given back to them to form their ain musical ideas as full participants in their musical development".[16]

Approaches to learning [edit]

The mechanical and factual elements of musical literacy tin be taught in an educational environment with 'music theory' and 'musicology' in order to use these "certain bits of articulate data... [to] trigger or actuate the right perceptual sets and interpretive frameworks".[17] The descriptive nature of both teaching how to read and write standard Western annotation (i.eastward. music theory),[18] and reading about the social, political, and historical contexts in which the music was written as well equally the ways in which information technology was practiced/performed (i.eastward. musicology),[xix] constitute the visual and reading/writing approaches to learning. While the "factual noesis and ability components... are developed culturally within a given social context",[20] signs and symbols on printed sheet music are also used for 'symbolic interaction'[21] "which enable [the musician] to understand [broader musical] discourse".[22] Asmus Jr. (2004)[23] proposes that "about educators would agree that... the ability to perform from musical notation is paramount";[24] that the only way to go a "better music reader... is to read music".[25]

Auditory learning is as — if not more (as claimed by Herbst, de Moisture & Rijsdijk, 2005[26]) — important, however, equally "neither the 'extramusical' nor the 'purely musical' content of [any piece of] music can come up across for a listener who brings nothing to it from [their] previous experience of related music and of the earth".[27] Listening is "through and through contextual: for the music to be heard or experienced... is for it to be related to — brought in some mode into juxtaposition with — patterns, norms, phenomena, facts, lying outside the specific music itself".[28] Auditory-oriented education teaches comprehensive listening and aural perception against the "backdrop of a host of norms associated with the manner, genre, and catamenia categories, and the individual compositional corpus".[29] This frames "appropriate reactions and registerings on the order of tension and release, or expectation and fulfillment, or implication and realization during the course of the music[al piece]".[thirty] Information technology is in this department that conventional classroom education often fails the individual in their acquisition of complete musical literacy every bit non simply have "researchers... pointed out that children coming to school do not have the foundational audible experiences with music to the extent that they have had with language",[31] but the "sectional concentration on reading [and thus lack of listening] has held back the progress of countless learners, while putting many others off completely".[32] Information technology is in this regard that musical literacy operates independently of music teaching equally — while affecting the outcome of an individual'south literacy — information technology is not defined by the quality of the education.

Furthermore, the kinesthetic aspect of music education plays a role in the achievement of musical literacy, as "human interaction is mediated by the use of symbols, by interpretation, [and] past ascertaining the pregnant of i another's actions".[33] "The different ways human emotions embody themselves in gesture and stance... sets of cultural associations carried by particular rhythms, motifs, timbres, and instruments... [and] aspects of a composer'due south life, work, and setting"[34] form both the musician'due south understanding of a piece of work'south historical context, too as any new meaning attached to information technology by its recontextualization in their contemporary musical settings and practices.

These aspects of musical literacy development coagulate into various educational practices that approach these types of visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic learning in different ways. Unfortunately, "fluent music literacy is a rarely acquired ability in... Western culture"[35] equally "many children are failed by the ways in which they are taught to read music".[36] Every bit such, many scholars debate over the best mode to approach musical teaching.

Pedagogy [edit]

For many scholars, the conquering of aural skills prior to learning the conventions of print music — a 'audio before symbol'[37] arroyo — serves as the "basis for making musical significant".[38] Much like pedagogical approaches in language development, Mills & McPherson (2015)[39] observe that "children should become competent with spoken verbal language [ie. aural skills] earlier they grapple with written verbal linguistic communication [ie. visual/written note skills]".[xl] For others, they find a 'language- and speech-based' arroyo more than effective, but only "afterward the basic structure and vocabulary of the linguistic communication has outset been established".[41] Gundmundsdottir[42] recommends that the "age of students should be considered when choosing a method for teaching"[43] given the changing receptiveness of a developing brain.

In-field research collated by Gudmundsdottir[44] on this topic notes that:

- "Methods using foot borer to marking the beat and counting or clapping the rhythm tin can exist highly constructive with older children and teenagers (Boyle 1970; Salzberg and Wang 1989) while the same method proves ineffective and distractive with 3rd and 4th graders (Palmer 1976; Salzberg and Wang 1989)";[45] and,

- "Methods using speech cues to identify and reproduce rhythmic patterns seem to be effective and appropriate for third and 4th graders (Bebeau 1982; Palmer 1976; Shehan 1987) also as for 6th graders (Shehan, 1987)."[46]

Moreover, Mills & McPherson[47] conclude that:

- "The general dominion recommended by McPherson and Gabrielsson (2002) is for children to learn to read pieces they already know by ear, before pieces they do not know which require more sophisticated levels of processing."[48]

Burton[49] constitute "play-based orientation... appeal[ed] to the natural fashion children learn[ed]",[l] and that the process of learning how to read, write, and play/verbalise music paralleled the process of learning linguistic communication.[51] Creating an outlet for the energy of children while using the conceptual framework of other schoolhouse classes to develop their understanding of print music appears to enrich all areas of brain development.[52] Equally such, Koopman (1996)[53] is of the opinion that "[the] rich musical feel alone justifies the pedagogy of music at schools".[54]

Stewart, Walsh & Frith (2004)[55] state that "music reading is an automatic process in trained musicians"[56] whereby the speed of data and psychomotor processing occurs at a high level (Kopiez, Weihs, Ligges & Lee, 2006).[57] The coding of visual information, motor responses, and visual-motor integration[58] make upwardly several processes that occur both dependently and independently of 1 some other; while "the ability to play by ear may have a moderate positive correlation to music reading abilities",[59] studies too demonstrate that concepts of pitch and timing are perceived separately.[sixty]

The development of pitch recognition also varies inside itself depending on the context of the music and what mechanical skills an instrument or setting may require. Gudmundsdottir[61] references Fine, Berry & Rosner[62] when she notes that "successful music reading on an musical instrument does non necessarily crave internal representations of pitch as sight-singing does"[63] and proficiency in one area does not guarantee skill in the other. The ability to link the sound of a note with its printed note counterpart is a cornerstone in highly adult musical readers [64] and allows them to 'read ahead' when 'sight-reading' a slice due to such audible recollections.[65] Less-developed readers — or, "button pushers"[66] — contrastingly overly-rely on the visual-mechanical processes of musical literacy [i.e., "going directly from the visual prototype to the fingering required [on the instrument]",[67] rather than an inclusive auditory/cultural understanding (i.e. how to likewise mind to and translate music in addition to the mechanical processes). While musically-literate and -illiterate individuals may be as-able to place singular notes, "the experts outperform the novices in their ability to place a group of pitches as a particular chord or scale... and instantly translate that knowledge into a motor output".[68]

Contrastingly, "rhythm production is [universally] difficult without auditory coding"[69] as all musicians "rely on internal mental representations of musical metre [and temporal events] every bit they perform".[lxx] In the context of reading and writing music in the schoolhouse classroom, Burton[71] saw that "[students] were making their ain sense of rhythm in print"[72] and would cocky-correct when they realised that their audible perception of a rhythmic pattern did not match what they had transcribed on the manuscript.[73] Shehan (1987)[74] notes that successful strategies for didactics rhythm — much like pitch — do good from the teachings of linguistic communication literacy, as "written patterns... associated with aural labels in the course of spoken language cues... [tend] to exist a successful strategy for teaching rhythm reading".[75]

Scholars, Mills & McPherson,[76] identified stages of development in reading music annotation and recommend correlating a pedagogical arroyo to a stage that is best-received by the neurological development/age of a student. For instance, encouraging immature beginners to invent their own visual representations of pieces they know aurally provides them with the "metamusical awareness that will enhance their progress toward agreement why staff notation looks and works the style it does".[77] Similarly, for children younger than six years old, translating prior audible knowledge of melodies into fingerings on an instrument (i.e. kinesthetic learning) sets the foundation for introducing visual notation later and maintains the 'fun' element of developing musical literacy.[78]

These stages of development in reading music notation are outlined past Mills & McPherson[79] every bit follows:

- "Features: the markings on the page that class the basis of notation. These involve awareness of the features of the lines and curves of the musical symbols and notes, and knowledge that they are both systematic and meaningful.

- Messages/musical notes and signs: Consistent interpretation of features allows the kid to attend to and recognize basic symbol units such as individual notes, clef signs, time signatures, dynamic markings, sharps, flats, and and then forth.

- Syllables/intervals: Structural assay of melodic patterns involves recognizing the systematic relationships between adjoining notes (due east.g., intervals).

- Words/groups: The transition from individual notes to groups of notes occurs via structural assay of the component intervals, or past visual scanning of the whole musical thought (east.chiliad., chord, scale run). This represents the showtime level of musical meaning; yet, at this level, the meanings attached to individual clusters are decontextualized and isolated.

- Give-and-take groups/motifs or note grouplets: Combinations of clusters form a motif or motif grouplet, a level of musical pregnant equivalent to understanding individual phrases and clauses in text. These may vary in length according to their musical function.

- Idea/musical phrase or figure: In music, an private thought is expressed by combining motifs into a musical phrase.

- Main idea/musical idea: The combination of musical phrases yields a musical idea, equivalent in text-processing terms to the construction of a main thought from a paragraph.

- Themes/musical discipline: Understanding of the musical subject involves imposing a sense of musicality onto the score such that the component musical phrase and subject field are taken beyond technical proficiency to include variations of sound, mood, dynamics, and and then forth in ways that allow for individualized interpretation of the score (Cantwell & Millard, 1994, pp. 47–nine)."[80]

In that location are various schools of thought/pedagogy that translate these principles into practical teaching methods. The aim of many pedagogical approaches that also attempt to simultaneously address the "deficiency in enquiry that considers the ability to read and write music with musical comprehension [ie. cultural-historical knowledge in the context of visual and auditory learning] as a developmental domain".[81] I of these most well-known instruction frameworks is the 'Kodaly Method'.

The Kodaly Method [edit]

Zoltán Kodály claims that there are iv fundamental aspects to a musician that must develop both simultaneously and at the same rate in gild to reach fluent musical literacy; "(1) a well-trained ear, (2) a well-trained intellect, (3) a well-trained heart (aesthetic/emotional agreement), and (4) well-trained hands (technique)".[82] He was one of the first educators to claim that music literacy involved "the ability to read and write musical notation and to read notation at sight without the aid of an instrument... [also as] a person's noesis of an appreciation for a wide range of musical examples and styles".[83]

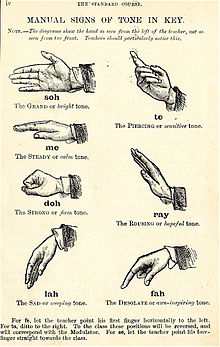

Kodály's education techniques utilise elements from language and the educational construction of language development to complement pedagogical efforts in the field of musical literacy development. In rhythm, the Kodály method assigns 'names' — originally adapted from the French time-name system pioneered by Paris-Chevé and Galin — to trounce values; correlating the number of beats in a notation to the number of syllables in its respective name.

Analogous to rhythm, the Kodaly method uses syllables to represent the sounds of notes in a scale as a mnemonic device to train singers. This technique was adapted from the teachings of Guido d'Arezzo, an 11th-century monk, who used the tones, 'Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, And so, La' from the 'Hymn to St. John' (International Kodaly Guild, 2014) as syllabic representations of pitch. The idea in contemporary Kodály educational activity is that each consequent pitch in a musical calibration is assigned a syllable:

1 2 three iv 5 6 vii 8/1

Doh Ray Me Fah Soh Lah Te Doh

This can exist applied in 'Absolute' (or, 'Stock-still-Doh') Class — as well known every bit 'Solfege' — or in a 'Relative' (or, 'Movable-Doh') Form — likewise known as 'Solfa' — where 'Doh' starts on the outset pitch of the scale (i.e. for A Major, 'Doh' is 'A'; for M Major, 'Doh' is 'G'; East Major, 'Doh' is 'Due east'; and and then on).

The piece of work of Sarah Glover and (continued by) John Curwen throughout England in the 19th Century meant that 'Moveable-Doh' solfa became the "favoured pedagogical tool to teach singers to read music".[84] In add-on to the auditory-linguistic aid of syllable-to-pitch, John Curwen also introduced a kinesthetic element where different mitt signs were applied to each tone of the scale.

Csikos & Dohany[85] affirm the popularity of the Kodály method over history and cite Barkoczi & Pleh[86] and Hallam[87] on "the powerfulness of the Kodály method in Hungary... [and] abroad"[88] in the context of achieving musical literacy inside the schoolhouse curriculum.

Braille music literacy [edit]

Methods such as Kodály'south, notwithstanding — which rely on audio to inform the visual chemical element of conventional staff notation — fall short for learners who are unable to meet. "No matter how brilliant the ear and how good the memory, literacy is essential for the blind student likewise",[89] and unfortunately conventional staff note fails to cater to visually-impaired needs.

To rectify this, enlarged print music or Braille music scores can be supplied to depression vision, legally blind, and totally bullheaded individuals so that they can supplant the visual attribute of learning with a tactile one (i.due east. enhanced kinesthetic learning). According to Conn,[90] in club for blind students to "fully develop their audible skills... fully participate in music... become an contained and lifelong learner... have a chance to completely analyse the music... make full use of [their] own interpretive ability... share [their] composition... [and] gain employment/career path",[91] they must larn how to read and write Braille music.

Not unlike sighted educational activity, teaching students how to read language in braille parallels the pedagogy of braille musical literacy. Toussaint & Tiger[92] cite Mangold[93] and Crawford & Elliott [94] on the "novel relation between the tactile stimulus (i.eastward., a braille symbol) and an auditory or vocal stimulus (i.e., the spoken letter name)".[95] This mirrors Kodály'south visual (i.e., conventional staff annotation)-to-auditory (i.e., similarly, the spoken letter of the alphabet name) approach in music education.

Despite the pedagogical similarities, all the same, Braille music literacy is far lower than musical literacy in sighted individuals. In this sense, likewise, the comparative percentage of sighted versus blind individuals who are literate in language versus music, are on an equal trajectory — for instance, linguistic communication literacy for sighted year five school students in Australia is at 93.ix%[96] compared to a 6.55% charge per unit of HSC students studying music,[97] while language literacy for blind individuals is at approximately 12%.[98] Ianuzzi[99] comments on these double standards when she asks, "How much music would students acquire to play if their music teachers couldn't read the notes? Unfortunately, not very many teachers of blind children are fluent in reading and writing Braille themselves."[100]

Although the core of musical literacy is arguably in relation to "extensive and repeated listening",[101] "there is however a demand for explicit theories of music reading that would organise knowledge and research nearly music reading into a system of assumptions, principles, and procedures"[102] that would benefit poor-to-nil vision individuals. Information technology is via the fundamental elements of reading literacy and "the power to empathise the majority of... utterances in a given tradition"[103] that musical literacy can exist achieved.[104]

However, sighted or non, the diverse teaching methods and learning approaches required to attain musical literacy evidence the spectrum of psychological, neurological, multi-sensory, and motor skills functioning within an individual when they come into contact with music. Many fMRI studies take correspondingly demonstrated the bear upon of music and avant-garde music literacy on brain development.

Encephalon development [edit]

Both the processing of music and operation with musical instruments require the involvement of both hemispheres of the brain.[105] Structural differences (i.e. increased greyness matter) are found in the brain regions of musical individuals which are both directly linked to musical skills learned during instrumental preparation (e.g. independent fine motor skills in both hands, auditory discrimination of pitch), and also indirectly linked with improvements in linguistic communication and mathematical skills.[106]

Many studies demonstrate that "music tin can have constructive outcomes on our mindsets that may make learning simpler".[107] For instance, young children exhibited a 46% increase in spatial IQ — essential for higher heed capacities involving complex arithmetic and science — afterward developing aspects of their musical literacy.[108] Such mathematical skills are enhanced in the brain due to the spatial training involved in learning music note because "understanding rhythmic annotation actually requires math-specific skills, such as pattern recognition and an understanding of proportion, ratio, fractions, and subdivision [of note values]".[109]

Superior "dialect chapters, including vocabulary, expressiveness, and simplicity of correspondence"[110] tin can also be seen in musically-literate individuals. This is due to "both music and language processing requir[ing] the ability to segment streams of audio into small perceptual units".[111] Research confirms the relationship between musical literacy and reading and reasoning,[112] too as non-cognitive skills such equally leisure and emotional development,[113] coordination and innovativeness, attention and focus, memory, creativity, self-conviction, and empathetic interpersonal relationships.[114] Due to these diverse factors and impacts, Williams (1987)[115] finds herself of the opinion that "[musical] literacy gives nobility also as competence, and is of the utmost importace to self-prototype and success... [it gives the] great joy of learning... the thrill of participation, and the satisfaction of informed listening".[116]

References [edit]

- ^ Swanwick, 1999, as cited in Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.6

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.24

- ^ Levinson, 1990; Csapo, 2004; Waller, 2010; Hodges & Nolker, 2011; Burton, 2015; Mills & McPherson, 2015; Csikos & Dohany, 2016

- ^ Wolf, 1976, every bit cited in Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.4

- ^ Csíkos, G.; Dohány (2016), "Connections between music literacy and music-related background variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Research in Music Education, 28, ISSN 1938-2065

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.five

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.2

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.3

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.2

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.5

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.2

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.iii

- ^ Waller, D (2010). "Linguistic communication Literacy and Music Literacy". Philosophy of Music Education Review. 18 (i): 26–44. doi:x.2979/pme.2010.18.one.26. S2CID 144062517.

- ^ Burton, 2015, p.9

- ^ Waller, 2010, as cited in Burton, 2015, p.9

- ^ Burton, 2015, p.9

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.26

- ^ Levinson, 1990; Burton, 2015

- ^ Csapo, 2004; Levinson, 1990; Csikos & Dohany, 2016

- ^ Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.3

- ^ Blumer, H (1986). "Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method". Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.18

- ^ Asmus Jr., Edward P. (Spring 2004), "Music Teaching and Music Literacy", Journal of Music Teacher Education, SAGE Publications, 13 (2): half dozen–8, doi:10.1177/10570837040130020102, S2CID 143478361

- ^ Asmus Jr., Edward P. (Spring 2004), "Music Teaching and Music Literacy", Periodical of Music Teacher Pedagogy, SAGE Publications, 13 (2): vii, doi:x.1177/10570837040130020102, S2CID 143478361

- ^ Asmus Jr., Edward P. (Jump 2004), "Music Teaching and Music Literacy", Periodical of Music Teacher Educational activity, SAGE Publications, 13 (2): 8, doi:10.1177/10570837040130020102, S2CID 143478361

- ^ Herbst, A; de Wet, J; Rijsdijk, S (2005). "A survey of music pedagogy in the master schools of South Africa's Cape Peninsula". Periodical of Enquiry in Music Education. 53 (3): 260–283. doi:x.1177/002242940505300307. S2CID 144468948.

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.23

- ^ Gombrich, 1963; Wollheim, 1968, 1980; Goodman, 1968; Walton, 1970; Sagoff, 1978; Pettit in Schaper, 1983

- ^ Meyer, 1956; Meyer, 1967

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.20

- ^ Burton, 2015, p.4

- ^ McPherson, 1993, 2005; Mills, 1991b,c, 2005; Priest, 1989; Schenck, 1989; every bit cited in Mills & McPherson, 2015, p.189

- ^ Blumer, 1986, p.79, as cited in Burton, 2015

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.23

- ^ Light-green, 2002, as cited in Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.1

- ^ Mills & McPherson, 2006, as cited in Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.1

- ^ McPherson & Gabrielsson, 2002; Mills & McPherson, 2006; Gordon, 2012; Mills & McPherson, 2015

- ^ Burton, 2015, pp.i-2

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, 1000. (2015), "Chapter ix. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child as musician: A handbook of musical evolution, Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 1–16, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Adams (1994) & Kirby (1988) in Mills, J.; McPherson, K. (2015), "Chapter ix. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development, Oxford Scholarship Online, p. 179, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Cooper, 2003, every bit cited in Mills & McPherson, 2015, p.177

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading enquiry", Music Educational activity Inquiry, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading research", Music Education Enquiry, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading inquiry", Music Educational activity Research, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading inquiry", Music Education Research, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:x.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading enquiry", Music Education Enquiry, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, G. (2015), "Chapter 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child every bit musician: A handbook of musical development, Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 1–sixteen, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, Thou. (2015), "Chapter 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child every bit musician: A handbook of musical evolution, Oxford Scholarship Online, p. 180, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Burton, Southward. (2015), "Making music mine: the development of rhythmic literacy", Music Education Research, Taylor & Francis Online, 19 (2): 133–142, doi:x.1080/14613808.2015.1095720, S2CID 147486278

- ^ Burton, S. (2015), "Making music mine: the development of rhythmic literacy", Music Instruction Research, Taylor & Francis Online, nineteen (2): 133–142, doi:x.1080/14613808.2015.1095720, S2CID 147486278

- ^ Burton, 2011; Gordon, 2012; Gruhn, 2002; Pinzino, 2007; Reynolds, Long & Valerio, 2007

- ^ Burton, S. (2015), "Making music mine: the development of rhythmic literacy", Music Education Research, Taylor & Francis Online, 19 (ii): 133–142, doi:x.1080/14613808.2015.1095720, S2CID 147486278

- ^ As cited in Csíkos, One thousand.; Dohány (2016), "Connections betwixt music literacy and music-related background variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Research in Music Education, 28: 4, ISSN 1938-2065

- ^ Csíkos, K.; Dohány (2016), "Connections between music literacy and music-related background variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Research in Music Pedagogy, 28: 4, ISSN 1938-2065

- ^ Equally cited in Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading research", Music Didactics Research, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:ten.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading inquiry", Music Didactics Inquiry, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ As cited in Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading research", Music Education Research, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2007). Error analysis of immature piano students' music reading performances. Paper presented at the eighth conference of the Club for Music Perception and Noesis. Concordia University, Montreal.

- ^ Luce, 1965; Mishra, 1998

- ^ Schön & Besson, 2002; Waters, Townsend & Underwood, 1998

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading research", Music Education Research, 12 (4): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- ^ Fine, P; Drupe, A; Rosner, B (2006). "The outcome of pattern recognition and tonal predictability on sight-singing ability". Psychology of Music. 34 (4): 431–447. doi:10.1177/0305735606067152. S2CID 145198686.

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading enquiry", Music Education Research, ResearchGate, 12(iv): 2, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809

- ^ McPherson, 1993, 1994b, 2005; Schleuter, 1997

- ^ Mills & McPherson, 2015, p.181

- ^ Schleuter, 1997

- ^ Mills & McPherson, 2015, p.181

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.vi

- ^ Dodson, 1983, p.iv

- ^ Palmer & Krumhansl, 1990; Sloboda, 1983; equally cited in Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.9

- ^ Burton, Due south. (2015), "Making music mine: the evolution of rhythmic literacy", Music Teaching Research, Taylor & Francis Online, 19 (2): 133–142, doi:x.1080/14613808.2015.1095720, S2CID 147486278

- ^ Burton, 2015, pp.6-vii

- ^ Burton, 2015, p.6

- ^ Every bit cited in Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.10

- ^ Gudmundsdottir, 2010, p.10

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, M. (2015), "Chapter 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child every bit musician: A handbook of musical development, Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 1–sixteen, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ McPherson & Gabrielsson, 2002; Upitis, 1990, 1992; equally cited in Mills & McPherson, 2015, p.180

- ^ McPherson & Gabrielsson, 2002

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, K. (2015), "Chapter 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development, Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 1–16, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Mills, J.; McPherson, G. (2015), "Chapter 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The kid as musician: A handbook of musical evolution, Oxford Scholarship Online, p. 182, ISBN9780198530329

- ^ Burton, 2015, p.one

- ^ Bonis, 1974, p.197

- ^ International Kodaly Guild, 2014

- ^ International Kodaly Society, 2014

- ^ Csíkos, G.; Dohány (2016), "Connections betwixt music literacy and music-related groundwork variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Inquiry in Music Instruction, 28, ISSN 1938-2065

- ^ Barkóczi, I; Pléh, C (1977). Psychological examination of the Kodály method of musical instruction. Kecskemét, Hungary: Kodály Intézet.

- ^ Hallam, S (2010). "The ability of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people". International Periodical of Music Education. 28 (3): 269–289. doi:10.1177/0255761410370658. S2CID 5662260.

- ^ Csíkos, G.; Dohány (2016), "Connections between music literacy and music-related groundwork variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Research in Music Education, 28: 4, ISSN 1938-2065

- ^ Cooper, 1994, as cited in Conn, 2001, p.four

- ^ Conn, J. (2001), "Braille Music Literacy", Annual Conference of the Australian Braille Authority, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 1–4

- ^ Conn, J. (2001), "Braille Music Literacy", Braille Music Literacy, Annual Briefing of the Australian Braille Authority, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 2–iii

- ^ Toussaint, One thousand. A.; Tiger, J. H. (2010). "Teaching early on braille literacy skills within a stimulus equivalence paradigm to children with degenerative visual impairments". Journal of Practical Behavior Assay. 43 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-181. PMC2884344. PMID 21119894.

- ^ Mangold, S. S. (1978). "Tactile perception and braille letter of the alphabet recognition: Effects of developmental teaching". Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness. 72: 259–266.

- ^ Crawford, S; Elliott, R. T. (2007). "Assay of phonemes, graphemes, onset-rimes, and words with braille-learning children". Periodical of Visual Impairment & Blindness. 101 (9): 534–544. doi:10.1177/0145482X0710100903. S2CID 141528094.

- ^ Toussaint, K. A.; Tiger, J. H. (2010). "Teaching early braille literacy skills within a stimulus equivalence paradigm to children with degenerative visual impairments". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 43 (2): 182. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-181. PMC2884344. PMID 21119894.

- ^ Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, 2017

- ^ Hoegh-Guldberg, Hans (2012). "Music Education Statistics".

- ^ Touissant & Tiger, 2010, p.181. In that location are no figures to prove how low musical literacy is for this variable

- ^ Ianuzzi, J (1996). "Braille or Print: Why the contend?". Hereafter Reflections. 15 (1).

- ^ Ianuzzi, J (1996). "Braille or Print: Why the debate?". Future Reflections. 15 (1).

- ^ Levinson, 1990, p.26

- ^ Hodges & Nolker, 2011, p.fourscore

- ^ Levinson 1990, p.xix

- ^ Hirsch, 1983, on "cultural literacy"; as cited in Levinson 1990, p.19

- ^ Sarker & Biswas, 2015; Norton, 2005, as cited in Ardila, 2010, p.108

- ^ Schalug, Norton, Overy & Winner, 2005, pp.221, 226

- ^ Sarker & Biswas, 2015, p.108

- ^ Sarker & Biswas, 2015, p.109

- ^ Schlaug, Norton, Overy & Winner, 2005, p.226

- ^ Sarker & Biswas, 2015, p.110

- ^ Schlaug, Norton, Overy & Winner, 2005, p.226

- ^ Weinberger, 1998, as cited in Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.4

- ^ Pitts, 2000, as cited in Csikos & Dohany, 2016, p.4

- ^ Sarkar & Biswas, 2015, p.110

- ^ As cited in Conn, 2001, p.four

- ^ Every bit cited in Conn, 2001, p.iv

Bibliography [edit]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017). "Children'south Headline Indicators: Literacy".

- Ardila, A (2010). "Illiteracy: The Neuropsychology of Cognition Without Reading". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 25 (8): 689–712. doi:10.1093/arclin/acq079. PMID 21075867.

- Asmus Jr., Edward P. (Spring 2004), "Music Teaching and Music Literacy", Periodical of Music Instructor Instruction, SAGE Publications, 13 (ii): 6–8, doi:10.1177/10570837040130020102, S2CID 143478361

- Barkóczi, I; Pléh, C (1977). Psychological examination of the Kodály method of musical education. Kecskemét, Hungary: Kodály Intézet.

- Bonis, F, ed. (1974). The Selected Writings of Zoltan Kodaly. London: Boosey and Hawkes.

- Blumer, H (1986). "Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method". Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Burton, S. L. (2011). "Language Acquisition: A Lens on Music Learning". In Burton, South. L.; Taggart, C. C. (eds.). Learning from Young Children: Research in Early Childhood Music. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Teaching. pp. 23–38.

- Burton, South. (2015), "Making music mine: the development of rhythmic literacy", Music Education Research, Taylor & Francis Online, xix (two): 133–142, doi:10.1080/14613808.2015.1095720, S2CID 147486278

- Conn, J. (2001), "Braille Music Literacy", Annual Briefing of the Australian Braille Dominance, Brisbane, Commonwealth of australia, pp. 1–four

- Crawford, South; Elliott, R. T. (2007). "Analysis of phonemes, graphemes, onset-rimes, and words with braille-learning children". Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness. 101 (9): 534–544. doi:10.1177/0145482X0710100903. S2CID 141528094.

- Csapó, B (2004). "Knowledge and competencies". In Letschert, J (ed.). The integrated person: How curriculum evolution relates to new competencies. Enschede, Overijssel, Netherlands: CIDREE. pp. 35–49.

- Csíkos, One thousand.; Dohány (2016), "Connections betwixt music literacy and music-related background variables: An empirical investigation" (PDF), Visions of Research in Music Education, 28, ISSN 1938-2065

- Dodson, T. A. (1983). "Developing music reading skills: Research implications". Update. i (4): 3–6.

- Fine, P; Berry, A; Rosner, B (2006). "The effect of pattern recognition and tonal predictability on sight-singing ability". Psychology of Music. 34 (four): 431–447. doi:x.1177/0305735606067152. S2CID 145198686.

- Gombrich, E. H. (1963). "Expression and Communication". Meditations on a Hobby Horse. New York: Phaidon.

- Goodman, N (1968). Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Gordon, Due east. E. (2012). Learning Sequences in Music: Skill, Content, and Patterns. Chicago, IL: GIA.

- Gruhn, W (2002). "Phases and Stages in Early Music Learning: A Longitudinal Study on the Evolution of Young Children's Musical Potential". Music Education Inquiry. four (1): 51–71. doi:10.1080/14613800220119778. S2CID 146293664.

- Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2007). Error assay of young piano students' music reading performances. Paper presented at the 8th conference of the Gild for Music Perception and Noesis. Concordia Academy, Montreal.

- Gudmundsdottir, H. R. (2010), "Advances in music-reading enquiry", Music Education Research, 12 (four): 331–338, doi:10.1080/14613808.2010.504809, S2CID 143530523

- Hallam, S (2010). "The power of music: Its touch on on the intellectual, social and personal evolution of children and young people". International Journal of Music Education. 28 (iii): 269–289. doi:10.1177/0255761410370658. S2CID 5662260.

- Herbst, A; de Moisture, J; Rijsdijk, S (2005). "A survey of music education in the primary schools of South Africa's Cape Peninsula". Journal of Research in Music Education. 53 (3): 260–283. doi:ten.1177/002242940505300307. S2CID 144468948.

- Hodges, D; Nolker, B (2011). "The Acquisition of Music Reading Skills". In Colwell, R; Webster, P (eds.). MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning. New York: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 61–91.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, Hans (2012). "Music Didactics Statistics".

- Ianuzzi, J (1996). "Braille or Impress: Why the debate?". Future Reflections. 15 (1).

- International Kodaly Social club (2014). "Musical Literacy".

- Levinson, J. (1990), "Musical Literacy", The Journal of Aesthetic Pedagogy, Jstor, 24 (1): 17–30, doi:x.2307/3332852, JSTOR 3332852

- Luce, J. R. (1965). "Sight-reading and ear-playing abilities as related to instrumental music students". Journal of Research in Music Didactics. 13 (2): 101–109. doi:ten.2307/3344447. JSTOR 3344447. S2CID 145343012.

- Mangold, Southward. S. (1978). "Tactile perception and braille letter recognition: Effects of developmental teaching". Journal of Visual Harm and Incomprehension. 72: 259–266.

- McPherson, G; Gabrielsson, A (2002). "From Sound to Sign". In Parncutt, R; McPherson, G (eds.). The Science and Psychology of Music Performance: Artistic Strategies for Education and Learning. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 99–116.

- McPherson, Thou. E. (1993). "Factors and abilities influencing the development of visual, audible, and creative performance skills in music and their educational implications (Doctoral dissertation)". Dissertation Abstracts International. 54/04-A, 1277 (University Microfilms No. 9317278) – via Academy of Sydney, Australia.

- McPherson, Grand. East. (1994b). "Improvisation: Past, present and future". In Lees, H (ed.). Musical connections: Tradition and change. Tampa, Florida, Usa: Proceedings of the 21st World Conference of the International Guild for Music Education. pp. 154–162.

- McPherson, K. E. (2005). "From child to musician: Skill development during the beginning stages of learning an instrument". Psychology of Music. 33 (1): v–35. doi:10.1177/0305735605048012. S2CID 144543756.

- Meyer, 50 (1956). Emotion and Significant in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Meyer, 50 (1967). Music, the Arts, and Ideas. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press.

- Meyer, Fifty (1973). Explaining Music. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Mills, J; McPherson, G (2006). "Musical Literacy". In McPherson, G (ed.). The Kid equally Musician: A Handbook of Musical Development. New York: Oxford University Printing. pp. 155–172.

- Mills, J.; McPherson, G. (2015), "Affiliate 9. Musical Literacy: Reading traditional clef notation" (PDF), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development, Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 1–xvi, ISBN9780198530329

- Mishra, J (1998). Factors influencing sight-reading ability. Paper presented at the Music Educator‟s National Conference. Phoenix, Arizona.

- Pettit, P (1983). "The Possibility of Artful Realism". In Schaper, E (ed.). Pleasure, Preference, and Value. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pinzino, M. E. (2007). Messages on Music Learning. Homewood, IL: Come Children Sing Found.

- Reynolds, A. Thousand.; Long, S; Valerio, W. H. (2007). "Linguistic communication Conquering and Music Acquisition: Possible Parallels". In Smithrim, 1000; Upitis, R (eds.). Mind to Their Voices: Research and Do in Early Babyhood Music. Toronto: Canadian Music Educators Clan. pp. 211–227.

- Sagoff, M (1978). "Historical Authenticity". Erkenntnis. 12. doi:ten.1007/bf00209917. S2CID 189887849.

- Sarker, J; Biswas, U (2015). "The role of music and the encephalon development of children" (PDF). The Pharma Innovation Journal. four (8): 107–111. ISSN 2277-7695.

- Schlaug, Thousand; Norton, A; Overy, K; Winner, E (2005). "Effects of Music Training on the Child's Brain and Cognitive Development" (PDF). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1060 (1): 219–229. Bibcode:2005NYASA1060..219S. doi:10.1196/annals.1360.015. PMID 16597769. S2CID 7320751.

- Schleuter, Southward (1997). A sound approach to pedagogy instrumentalists (second ed.). New York: Schirmer Books.

- Schön, D; Besson, M (2002). "Processing pitch and duration in music reading: a RTERP study". Neuropsychologia. 40 (7): 868–878. doi:ten.1016/S0028-3932(01)00170-1. PMID 11900738. S2CID 18515997.

- Toussaint, K. A.; Tiger, J. H. (2010). "Teaching early braille literacy skills within a stimulus equivalence paradigm to children with degenerative visual impairments". Periodical of Applied Behavior Analysis. 43 (two): 181–194. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-181. PMC2884344. PMID 21119894.

- Waller, D (2010). "Language Literacy and Music Literacy". Philosophy of Music Education Review. 18 (1): 26–44. doi:10.2979/pme.2010.18.one.26. S2CID 144062517.

- Walton, K (1970). "Categories of Fine art". Philosophical Review. 79 (3): 334–367. doi:ten.2307/2183933. JSTOR 2183933.

- Waters, A. J.; Townsend, East; Underwood, G (1998). "Expertise in musical sight reading: A study of pianists". British Journal of Psychology. 89: 477–488. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1998.tb02676.x.

- Wollheim, R (1980). Art and Its Objects. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_literacy

0 Response to "Percentage of People That Can Read Sheet Music"

Post a Comment